How to write a (almost generic) Makefile

I am not a big fan of IDEs. They are too big, too slow, too stiff. And to proper configure them is often a pain in the a**.

So most of the time I just use a fancy text editor to code my stuff (and I am currently trying to stick to vim, but that’s another story).

If you use a text editor instead of an IDE, you will recognize how much work the IDE does for you.

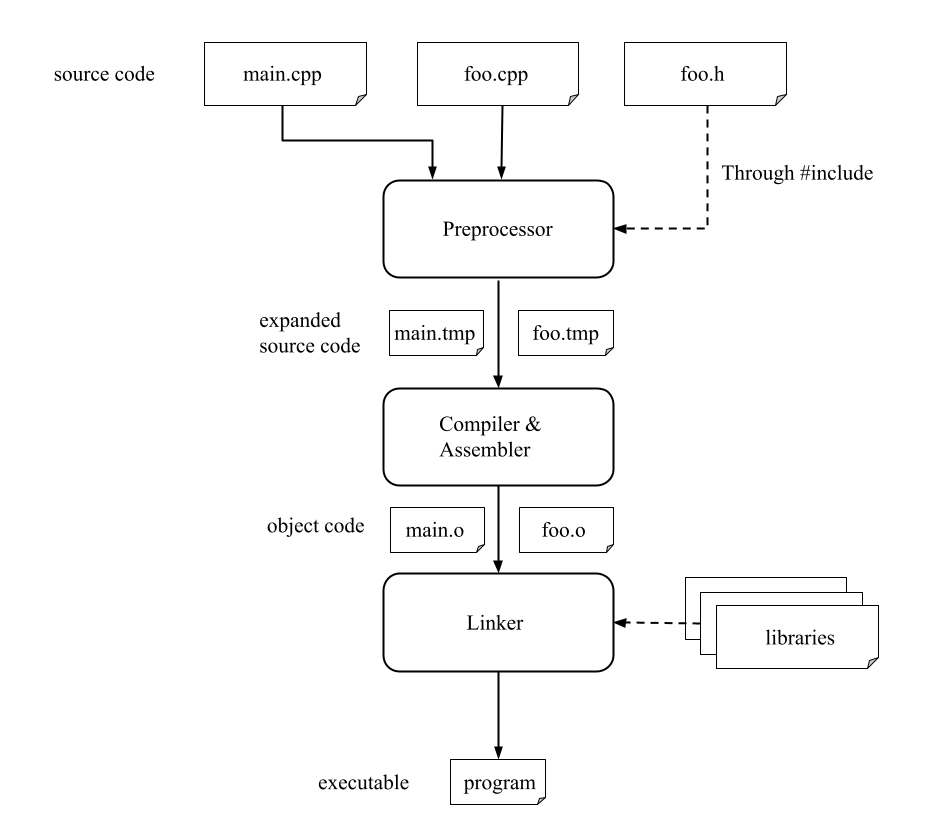

In this post I want to talk about the (C++) compiler and how to write a Makefile. The compiler takes the source files and turns them into an executable program.

If you use an IDE and write a fancy program, running the program is easy because all you have to do is click a button.

But if you are using a text editor, you have to pass your files to the compiler yourself. This is easy if you have just one file, but large projects consists of a lot of files and (above all) third party libraries.

You don’t want to pass the code of such large projects to the compiler by hand. That’s where Makefiles come in handy.

To explain how to write the Makefile, I first want to take a deeper look with you on how the compiler works.

How the compiler spreads its magic

Lets assume we have a large project with multiple files and a few third party libraries. The compiler should take all code files and libraries and turn them into binary code. This binary code can then be executed by the processor.

The first step, that the compiler takes is the preprocessing:

The preprocessor takes the files and searches for preprocessor directives. These are marked with a hash sign at the beginning at a line.

Let’s look at two examples.

1

2

3

4

5

#define two 2

int foo() {

return two;

}

Here the preprocessor will replace the word “two” with the number “2” in line four.

1

2

3

4

5

#include "secondFile.hpp"

int foo() {

return secondFoo();

}

This is the interesting stuff. There is an include statement in the first line. This statement tells the preprocessor to take the content of secondFile.hpp and paste it in the file that has the include directive. So the include statement will be replaced with (in general) function declarations.

In this example the include statement gets replaced with the declaration of the secondFoo function.

The second step is the compiler and the assembler.

In this step the file is translated into an object file. An object file is (in most of the cases) a binary file that can be read by the processor. But there are some gaps (for example at the jump directives) that will be filled by the linker.

The last step is the linker.

The linker connects all object files as well as included libraries that are part of the projects and combines them into a single executable file.

I have tried to visualize the whole process with a pipeline.

Write a Makefile

Before we take a look at the Makefile, I want to show you how I organize my cpp projects (as this will be important later).

├─ bin

│ └─ prog1.out

├─ build

│ ├─ main.o

│ ├─ foo.o

│ └─ ...

├─ lib

│ └─ ...

├─ src

│ ├─ main.cpp

│ ├─ foo.cpp

│ ├─ foo.h

│ └─ ...

├─ Readme.md

└─ MakefileOn the main level I have four folders and (at least) one file. The Makefile. The bin folder contains the executable, the target program so to speak. The build folder contains all the object files that the compiler creates. We will (usually) not touch them, but the linker needs them. The lib folder contains any third party library. The src folder contains all .cpp and .h files. So any source file that we write goes in there.

So with that out of the way, we can take a look at how to write the Makefile.

Let’s take a look at the simplest case of a Makefile, as well as the output of it.

1

2

testFoo:

echo "Hello World"

$ make testFoo

echo "Hello World"

Hello WorldSo like I promised we kept it simple. We can define a function-like structure called “testFoo” (the name is variable, so you can use whatever you like). The name (testFoo) is called target. Below the target is the so called recipe. It acts like the function code. A target and its recipe makes a rule. If we now call the Makefile with the directive make and the target testFoo, make will execute the recipe and (in our case) print out “Hello World”.

Now we take a look at the syntax of a rule in general.

1

2

target: prerequisites

recipe

Like you can see, I have added one more detail. So to speak in general terms: We first define a target (a construct we would like to have build). The prerequisites acts as a list of dependencies, so constructs that have to exist (or have to be made first) before the target can be build. The recipe is a collection of instructions that have to be executed in order to create the target.

So with that in mind, we could start to write our own Makefile.

1

all: bin/prog1.out

If we now type “make all” in our terminal, the Makefile will execute our rule with the target all. We defined bin/prog1.out as a dependency for the target all, as make does not know how to produce the dependencie, it will throw an error. So know we have to add another rule, that tells make how to build the dependency. I will also introduce variables here, as they make our lifes a lot easier.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

COMPILER := g++

TARGET := bin/prog1.out

BINDIR := bin

OBJECTS := ...

LIBDIR := lib

$(TARGET): $(OBJECTS)

mkdir -p $(BINDIR)

$(COMPILER) $^ -o $(TARGET) -L $(LIBDIR)

all: $(TARGET)

So as you see, we could define a variable with

So defining the OBJECTS variable is the next thing on our ToDo list. After that I will explain in depth what’s going on in the recipe.

We know two things about our object files. First of all, they all are located in the folder build/ and they have the same name as our .cpp files (located in src/). So for each .cpp file in src/, we have a .o file in build/. With that in mind, we need the names of the .cpp files in src/ and just change the folder and the ending. Let me introduce five variables that will do this job.

1

2

3

4

5

SRCDIR := src

BUILDDIR := build

SOURCES := $(shell find $(SRCDIR) -type f -name *.cpp)

OBJECTFILES := $(SOURCES:.cpp=.o)

OBJECTS := $(patsubst $(SRCDIR)/%, $(BUILDDIR)/%, $(OBJECTFILES))

The meaning of the first two variables should be quite clear. They are just there so we don’t have to write our folder names over and over again.

The next variable SOURCES should contain all .cpp files in our project. So how do we archive this?

We can execute a bash command in our variable definition. The output of this command will be our value of the variable.

This is done via $(shell enterCommandHere). The command I use here looks something like this:

$ find src -type f -name *.cpp

src/main.cpp

src/foo.cppThe command find will output all files in the specified folder (src) with the filetype (-type) folder (f) and which matches the pattern (*.cpp).

So now our variable SOURCES looks something like this

The next variable is just an interim step. We will never use this variable in any of our rules.

Here we just replace the ending .cpp with .o. So the OBJECTFILES should look like this:

The last variable replaces the folder of our object files string. The folder part of the files (src/) should be replaced with build/. Therefor we use the make directive patsubst. I took the next paragraph from the gnu documentation.

$(patsubst pattern,replacement,text)Patsubst finds whitespace-separated words in text that match pattern and replaces them with replacement.

What we do with it, we take the variable OBJECTFILES search for “src" and replace that with “build".

So the variable OBJECTS should look like this: OBJECTS := build/main.o build/foo.o

With that in mind, let’s have a look at the recipe for our target. I will resolve the variables for now for a better understanding.

1

2

3

4

5

bin/prog1.out: build/main.o build/foo.o

mkdir -p bin

g++ $^ -o bin/prog1.out -L lib

all: bin/prog1.out

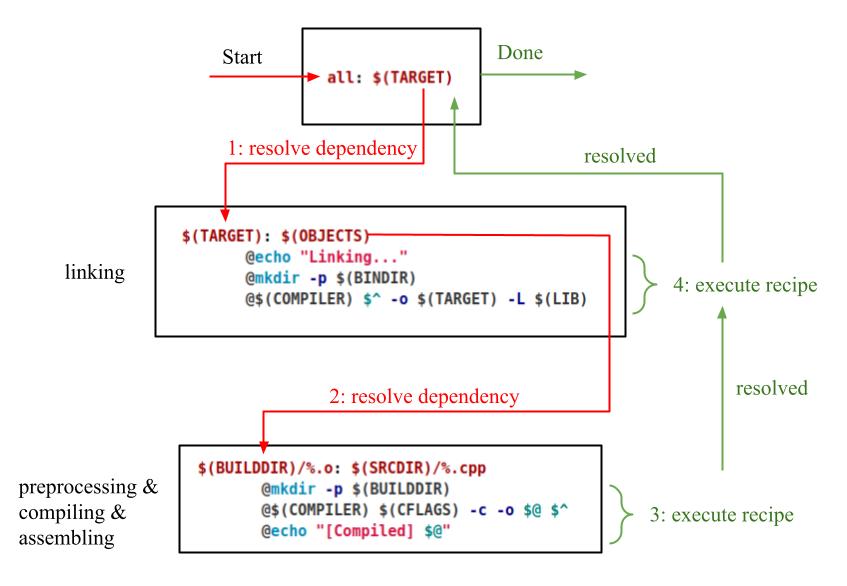

So let’s see what we have here so far. Our “gateway target” is all. The target “all” has the prerequisite “bin/prog1.out” (this will be our executable in the end).

Make will now search for a rule that produces “bin/prog1.out”. This rule is defined at line 1. The prerequisites for this rule are the object files that the linker needs.

Make will check if these object files are available at the given path, if not, it will again search for a rule to produce them.

Let’s assume for the moment that these object files exist and let us have a look at the recipe for the rule.

First of all we create the “bin” folder if it doesn’t exist (that’s what the “-p” parameter is for).

Then we call the linker with

But like I mentioned earlier, make will first look for a rule to build our object files. So we have to define another rule.

First we need a target that covers all object files. We could use our variable $(OBJECTS) for that, BUT, we need to call the compiler seperatly for every object file (unless there is an gcc option that I never noticed). One option to do that would be to define a rule for every object file we have. I (hopefully) don’t have to tell you why this is a bad idea.

A better option is, to define a rule with wildcards. For those who don’t know what wildcards are, they act like a placeholder. Just read the wiki, it is really straight forward.

So I just show you the rule and we can discuss it afterwards.

1

2

3

build/%.o: src/%.cpp

mkdir -p build

g++ -c -o $@ $^

So let’s see what we have here. Just assume make looks for a rule to produce “build/main.o”, make will match that with our defined rule, because the percentage sign will match any characters in any length.

The percentage sign in the prerequisite will be replaced with whatever has matched the target. So in the case of “build/main.o” the rule header will look something like this:

In the recipe we first create the build/ directory if it doesn’t exist.

We then call the compiler. The parameter “-c” tells g++ to preprocess, compile and assemble the file, but not link them. This is exactly what we want, because we will link them afterwards.

Like above we can define an output with the parameter “-o”. The name of the output file is the target of the rule (in our example case build/main.o). The target is represented by $@.

The file which should be compiled is defined at the end. The name of the file is the prerequisite of the target (in our example case src/main.cpp). Like in the rule above, the prerequisite is represented by “$^”. So the g++ command (in our example) would look something like this:

So let’s wrap the things up we did. If you read carefully, you might think that we have written our Makefile like a reverse compiler pipeline. But it is actually the compiler pipeline top to bottom.

Why? I have tried to visualize that in the following picture.

There is one more rule I would like to share with you.

clean:

rm -rf bin buildSo if you run “make clean” the executable as well as the object files will be deleted. This forces the next build to be a complete rebuild of the project. There are many situations where this comes in handy.

The last thing we should do (but it would work without it) is to define our phony targets. A phony target is a target which is not really a file. Our phony targets would be clean and all.

.PHONY: clean allTL;DR

For those of you who just are here for the Makefile:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

COMPILER := g++

TARGET := bin/prog1.out

LIB := lib

BINDIR := bin

SRCDIR := src

BUILDDIR := build

CFLAGS := -std=c++17 -O3

SOURCES := $(shell find $(SRCDIR) -type f -name *.cpp)

OBJECTFILES := $(SOURCES:.cpp=.o)

OBJECTS := $(patsubst $(SRCDIR)/%, $(BUILDDIR)/%, $(OBJECTFILES))

$(TARGET): $(OBJECTS)

@echo "Linking..."

@mkdir -p $(BINDIR)

@$(COMPILER) $^ -o $(TARGET) -L $(LIB)

$(BUILDDIR)/%.o: $(SRCDIR)/%.cpp

@mkdir -p $(BUILDDIR)

@$(COMPILER) $(CFLAGS) -c -o $@ $^

@echo "[Compiled] $@"

clean:

@echo "Let me clean that for you..."

@rm -rf $(BINDIR) $(BUILDDIR)

all: $(TARGET)

.PHONY: clean all

I’ve also added some console outputs. The @-signs at the beginning of a command supresses the output of the line to the console.

Keep hacking!